Toronto's "old town" district is a curious place. In general terms, its boundaries are Church Street in the west, Parliament Street in the east, Adelaide Street in the north, and perhaps the Esplanade to the south, if you include that section of the city that is actually filled in lake water, paved over after the railway arrived in Toronto in the 1850s.

It was here that the Town of York began, growing into the original downtown heart of the City of Toronto, up until 1899, when Toronto's new city hall (now known as "Old City Hall") became the centre of the municipal government. Through the twentieth century, Toronto's Old Town fell on hard times. By the 1920s, certainly, it had become an industrial urban backwater. By the middle of the 1900s, people were moving out of the downtown core and into the suburbs. The Old Town District, which had already fallen on hard times, only got worse. Some of our oldest buildings lay neglected, and forgotten as they were, they fell into disrepair and either fell apart or were demolished. During the 1960s, there was a mad rush to tear them all down. Why not? They were ugly, uninhabited eyesores, that had been neglected by all but the elements, and all that coal smoke in the air back one hundred years ago had blackened the exteriors of many one graceful Toronto landmarks.

But then in the 1970s, things began to change. People began to care more about built heritage. The Spadina Expressway proposal of the late 1960s was actually cancelled, part of the way into construction, because of fears that had been expressed by the public. The expressway would greatly increase noise and air pollution, create a heavy tax burden, and destroy parkland and homes. The fact that the expressway was due to run through a part of Cedarvale Park alarmed those amongst the population who were conservation minded, and this sense of preservation represented a new era in the city, where preservation of both natural and built heritage was okay. In the 1960s, thousands of heritage buildings in Toronto were destroyed, but the halting of the Spadina Expressway was like an epiphany of sorts; people started to care again and at least some of the old buildings were saved.

|

| THEN : The headlines in 1971 gave the news that construction of the Spadina Expressway would stop. It was a turning point, away from all the demolition of Toronto's heritage buildings through the 1960s, when thousands of heritage buildings were destroyed. The debate about the construction of the Spadina Expressway was a heated one, with some Torontonians calling out for the preservation of both green space and built heritage, and other groups, like construction workers, protesting at City Hall, in order to be given the opportunity to work. |

People started moving downtown again, too. A lot of factory buildings in the Old Town, and across southern Toronto, were salvaged and retrofitted, either as office space or new residential space. The Old Town District started to welcome new inhabitants, and today there is a mix of modern residential space, side by side with a few of the old fixtures that have survived. In many cases, the new condominium towers are even welcomed; they provide a new customer base for those businesses that run out of old buildings, and provide thousands of new neighbours who will fight to save local heritage, should the need arise in the future.

Wandering the streets of the Old Town District, there is one block of buildings that really leaps out. One block east of Jarvis Street, at George Street, on the north side of Adelaide Street East, there is a block of old buildings that have survived diminished prosperity, neglect, abandonment, and even fire, to rise from the ashes and be restored. They've been brought back to life and house successful, thriving businesses once again.

|

| THEN : The Bank of Upper Canada building, at George Street and Duke Street (now called Adelaide Street East) in 1872. |

|

| THEN : The historic block that contains the Bank of Upper Canada building (far left) in the late 1960s. |

|

| THEN : The Bank of Upper Canada building in 1977. |

|

| NOW : The Bank of Upper Canada building, on the northeast corner of George Street and Adelaide Street East, 2010. |

|

| NOW : The plaque outside the Bank of Upper Canada building briefly relates its history. |

Approaching this historic block of buildings from the west, one is greeted by the old Bank of Upper Canada building. The Bank of Upper Canada was the first major bank in early Ontario history. It was chartered on April 21, 1821, and first opened its doors in the Town of York in July of 1822. The business community of Upper Canada had been pressuring the government to start up a local bank, to provide capital for the growing province, and its capital in York. Like many early institutions, like the church community and the newspapers, and like the government itself, the Bank of Upper Canada was manipulated by the Family Compact, that group of wealthy landowners and governors who were the unofficial aristocracy of old Upper Canada. Its first president, William Allan, was president of the bank for over a decade, and generally led it well. He adapted the traditions of British banking theory to the frontier way of life in early Ontario. Later leaders in the management of the bank, particularly William Proudfoot, who was Allan's replacement, and Thomas Gibbs Ridout, who was the bank's cashier (a sort of general manager), were less successful. The policies of the Bank of Upper Canada throughout the 1830s were not terribly sympathetic to the needs of the emerging middle class, and this drove away some of those with local commercial interests, who began using other commercial banks instead. In the 1840s and 1850s, the Bank of Upper Canada relied heavily on the government accounts that it had, and began investing in the railways, making short term loans to help the construction of a railway system. There was an economic collapse in 1857, and the Bank of Upper Canada lost its account with the government in 1864; both of these were factors in the failure of the Bank of Upper Canada, which closed and ceased to exist as an institution in 1866.

|

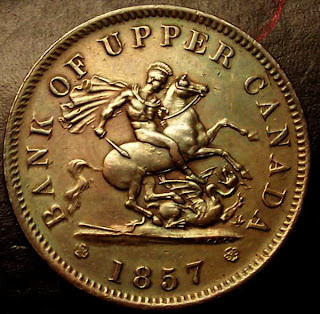

| NOW : Some of the surviving half penny coins issued by the Bank of Upper Canada in the 1850s. |

The building at George Street and Adelaide Street East was actually the second location of the Bank of Upper Canada. The first Bank of Upper Canada building was constructed on the southeast corner of King and Frederick Streets. The Bank of Upper Canada was originally housed in a store owned by William Allan, its first president, and one of the wealthiest men in the province. The central arched entrance to the building was off Frederick Street, and the building had windows on both the first and second floors. The institution that was the Bank of Upper Canada quickly outgrew this space, and the so the bank moved to the intersection of George Street and Adelaide Street East (then called Duke Street), in 1827. The first bank building, at Frederick and King streets, became a wholesale store, then a brewery, then a produce store and later, a boot store, until it was eventually demolished in 1915.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the area east of Jarvis Street had become very industrial. Today, Toronto's Distillery District ~ that quintessential industrial complex of Old Toronto ~ has been restored and converted into a popular cultural destination. The Canadian Opera Company has taken over an old gas refinery building off Front Street East, between Princess Street and Berkeley Street. But during the late 1800s and for much of the 1900s, the process worked in reverse. Old buildings which had been put up for far more graceful purposes were used as remnant buildings for various industrial processes. Two of the banks neighbours on Adelaide Street East were the 1833 post office and the 1822 home of Sir William Campbell. The post office, a few doors down to the east from the bank, was used as a management office when Christie had his bakery across on the south side of the street. Later, the post office was used as a cold storage facility for dairy products. Campbell's house, which stood at the top of Frederick Street on the north side of Adelaide Street East, was used for all sorts of purposes, including a nail factory. The old bank building was likewise the home of a variety of different installations.

The old home of Sir William Campbell was salvaged in 1972, and the entire house was put on the back of a flatbed truck and moved to Queen Street West and University Avenue, where it still stands today, saved from its original neighbourhood, restored to its former glories, and open as a museum. The old bank building, along with the post office, were left behind, stranded in their old neighbourhood and in rather threadbare and desultory condition. The end nearly came in the summer of 1978, when a fire broke out in the old block. This turn of events can either spell out the end for an old set of buildings, or act as a sort of catalyst for their revival. Fortunately, in this case, it was the latter. The block was saved and salvaged, with the 1833 post office reopened and a post office once again opening its doors in the location in 1983, exactly a century and a half after it was first built for that purpose. The Bank of Upper Canada building was restored, too, and has been home to a variety of private businesses every since.

The interior of the Bank of Upper Canada building is a mixture of preserved heritage features and modern interior design. The tenant on the main floor has brought in glass walls and shelving, but kept the original columns, which include both decorative Corinthian columns and large timbers that were originally hidden away behind the walls of the old building. Some of the original panelling has been saved, and a few of the interior window shutters have been kept. Up in the old attic of the Bank of Upper Canada, one of the tenants of the building have opened up the ceiling to show off some of the original timbers that helped to hold up the top of the building. Down in the basement, the original stone walls and arches have been saved, along with the basement's deep fireplaces. The building is, architecturally, a blend of both the old and the new.

Such is the nature of many of the historical buildings that have been restored or salvaged in Toronto. The only unfortunate part of the restoration of the Bank of Upper Canada building is that it is not largely accessible to the public. The tenants of the building, who supplied the means of its restoration and salvation, are all private companies. Alas, not everything can be turned into an interpretive museum, but at least the building itself has been saved. I recently had the opportunity to do a tour for the organization that leases the basement of the building, and took advantage of my chance to take some photographs.

|

| NOW : The stairwell leading down to the basement of the Bank of Upper Canada building. These days, the entrance to the basement is located off George Street. |

|

| NOW : The basement interior, showing the "gun loop" that may have been used to protect the vaults of the bank. The first Bank of Upper Canada building, on Frederick Street, did not have a custom built vault, so it was an important addition here, in the first real purpose built bank in the Town of York. |

|

| NOW : Detail of the gun loop. According to popular legend, the Bank of Upper Canada was considered a target for Mackenzie's Rebellion of 1837, but he never even came close to making it all the way to the bank building. |

|

| NOW : The basement of the Bank of Upper Canada today. |

|

| NOW : The arches of the old Bank of Upper Canada are amongst the details that have been preserved. |

|

| NOW : The basement of the Bank of Upper Canada originally contained some very deeply set and very large fireplaces. |

|

| NOW : Detail of a fireplace. |

|

| NOW : To the right of the door, the wiring for the light switch has been covered over and blended in with a thin layer of rough plaster like material. |

|

| NOW : Detail of the attempt to blend in the electrical work. |

|

| NOW : Brickwork detail. |

|

| NOW : The dry kitchen in the basement. During the renovation, new tenants were not allowed to break up the building to bring in water pipes. |

|

| NOW : A view of the basement, showing how the old has been preserved and blended into the new. |

|

| NOW : Another fireplace. |

|

| NOW : One of the restored doorways. |

|

| NOW : Old brickwork and modern interior design. |

|

| NOW : A basement doorway. |

|

| NOW : A panorama of the basement. |

|

| NOW : The Bank of Upper Canada building was expanded in 1851. Behind the expansion there is a small courtyard available for use by the modern day tenants of the building. |

|

| NOW : The back of the Bank of Upper Canada Building today. |

|

| NOW : A small plaque commemorates the 1851 addition to the building. |

_________________________________________________________

If you're interested in Toronto's "Old Town" Saint Lawrence Market neighbourhood, have a look at the information for my "Nineteenth Century Tour".

_________________________________________________________

Enjoyed the photos, Richard. Thanks for taking the time to do this. Dave

ReplyDeleteWas the Magdalen Asylum behind this building in 1877?

ReplyDeleteThank you for the informative content. Custom Homes in Toronto

ReplyDeleteSSh Reno well established and have a team of professional contractors that specialized on Home and Commercial Renovation Projects. Contact us now for free quotation.

ReplyDeleteReliable Renovation Contractor Singapore

Hacking Contractor Singapore