Everyone has heard the old expression that warns us how "those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it". But sometimes, it's hard to glean just what lessons history has to teach us. However, on occasion, history presents us with some very clear life hacks. Such was the case for John White, who made the mistake of sounding off a bit too loudly at a Christmas party that was held in the old Town of York, all the way back in December of 1799. Perhaps the lesson we could all learn from what happened next is that you should always mind your manners and rein in what you say, even at a Christmas party.

The Town of York was a pretty small place back then, stretching for a few blocks between George Street and Parliament Street, and from the lake at Front Street, north to Adelaide Street. What is now Queen Street was known as Lot Street, because it was from this thoroughfare that all the countryside estates, or lots, stretched north of the town. It's hard for us to envision a time when anything north of Queen Street was out in the wilds of the countryside and farmland north of town, but such was the case.

By the end of the 1790s, the Town of York was home to a few hundred people, and the population was something less than one thousand souls. Other than carving an existence and livelihood out of the wilderness, there wasn't much to do. Mail delivery was thin enough to be nearly non existent. There was a government issued newspaper, but newspapers of the day were only issued once a week, at best. News from the United Kingdom would take about two months to traverse the Atlantic. Keeping an eye on what our American neighbours were doing was more a source of consternation than entertainment, as witnessed by the fact that they would eventually cast an invading eye towards Upper Canada during the War of 1812. The first live theatrical shows in York didn't start up till about 1820. There wasn't even any WiFi.

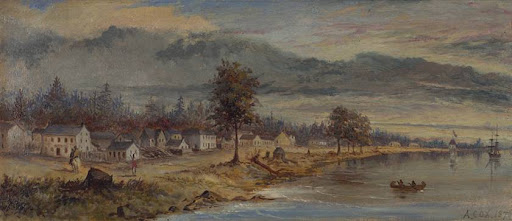

|

| The Town of York in 1803. |

So, gossip was an important part of everyday life. When the Province of Upper Canada was established back in 1791, it was supposed to be a microcosm of English traditions and institutions. We inherited a number of respectable customs, including English law and the Westminster style of government. But Upper Canada, and particularly its capital, York, were a lot more class aware at the end of the eighteenth century. Any sort of social snub was taken very seriously. A man named John White would soon find himself embroiled in the consequences of just such a matter.

John White was an English lawyer who was appointed the first Attorney General of Upper Canada, back in 1791. He came to Kingston that year, and then to Niagara region, before moving to York in 1797. It was John White who bore the responsibility of transferring British law to the colony of Upper Canada. Copies of his diary are held in the archives of the Law Society of Upper Canada, and his letters are housed at the National Archives of Canada. One would think that these would give us great insight into the province's early governance.

Instead, White used his diary to record little more than his social engagements. The letters that he wrote back to family and friends in England contained a litany of complaints, about his finances, his marriage, his wife, his health, the backwardness of the colony, the settlers, the threat of American invasion, the cost of construction, the weather, and what what he described as "the lack of rational society". In a letter to his brother-in-law, dated November of 1796, White described himself as "banished, solitary, hopeless, planted in the desert, disappointed and without prospect ..."

|

| This painting shows the very first meeting of the Legislature of Upper Canada, held back in 1791. John White is the second gentleman from the left, in the yellow waistcoat, and is circled. |

Things would only get worse for John White. He soon found an adversary in Major John Small, who was an officer in the militia, and who was appointed as the clerk of the province's Executive Council. This council served a similar function to the Cabinet back in England. It gave no account to the elected Legislative Assembly, and was often capable of exerting control over the province's early elected officials. Members of the Executive Council were also usually members of the Legislative Council, which acted similar to the United Kingdom's House of Lord, and which also had veto power over the Legislative Assembly.

John Small was praised by John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant Governor, as "a gentleman who possesses and is entitled to my highest confidence". It seems that Simcoe was one of the few people who actually held John Small in high regard. Small was often criticized for his inefficiency and poor job performance. Small drew a salary of £100 a year, which was less than the wage of some manual labourers, and little more than what Small's staff members made.

|

| John Small in his later years. |

The animosity between Small and White was not the result of professional strife, but rather came about due to unfounded gossip. Major Small’s wife, Elizabeth, had snubbed John White’s wife, Marianne, in public, at a time when social slights were taken very seriously. In turn, John White publicly insulted Small’s wife. According to some sources, White attended a Christmas party held at the end of 1799. It was on this occasion that he told a number of York’s finest that Elizabeth Small was lacking in moral fibre and marital fidelity.

|

| From everything I've read, Georgian parties sound as if they were heaps of fun. |

John White supposedly claimed that Elizabeth Small had actually been the former mistress of a British peer, Frederick Augustus Berkeley, the fifth Earl of Berkeley. Berkeley had supposedly tired of the relationship, and paid Small to take her off his hands, and carry her off to the colonies. The legality of John Small’s marriage was questioned, and there were even suggestions that White himself had slept with Mrs. Small.

|

| Frederick Augustus Berkeley, the fifth Earl of Berkeley, born 1745 and died 1810. |

Seeking to defend his wife’s reputation, John Small demanded satisfaction, and the two men met on an open field to the east of town on the morning of January 3, 1800. Presumably, both men had an opportunity to recover from whatever liquid revelry they'd downed at their lethal Christmas party. But, there was no recovering from the bad blood born between them - at least, not for John White. Perhaps John Small’s military experience gave him an advantage. He shot John White through the ribs, and White lingered in excruciating pain for 36 hours before dying on the evening of January 4th, 1800.

Authorities considered duelling to be a crime, and killing an opponent in a duel was legally the equivalent of murder. However, the laws were irregularly enforced. In early New France, several duellists were imprisoned, banished or executed. Sometimes, even the bodies of men killed in duels were desecrated. Under English law, juries consistently refused to convict duellists if they felt that the encounters had somehow been conducted fairly and honourably. John Small stood trial for the murder of John White – who was, after all, the province’s Attorney General – but was acquitted. His reputation, and that of his wife, suffered for a while, but he remained in York until his death in 1831.

______________________________________________

John Small’s house in York was dubbed “Berkeley House”, in a reference to the town of Berkeley, in England, where Small had been born. It stood at the southwest corner of King Street and Berkeley Street, which took its name from the house. When Small purchased it in 1795, it was nothing more than a simple wood cabin, but Small renovated and expanded it several times. John Small had a total of five sons, and after his death in 1831, his youngest son, Charles Coxwell Small, took over Berkeley House.

Charles Small had Berkeley House converted into a relatively standard Georgian style home. The house had a central portico extending out from the centre, and a gabled wing on either side. In fact, Charles Small renovated Berkeley House so thoroughly, that it bore little resemblance to the log cabin that his father had purchased back in in 1795.

|

| Berkeley House in 1885. |

Inside, at the height of its glory, the house contained a total of thirteen rooms, and outside the exterior of the house was surrounded by a fenced in garden. John Small had suffered socially because of his role in the duel of 1800, but by the time that his son Charles owned the house, the social stigma had been forgotten. Charles hosted a number of parties at Berkeley House, and it was the centre of the social scene for the gentry of the old Town of York and early City of Toronto.

|

| Inside Berkeley House, 1900. |

|

| Elizabeth Small |

Charles Smith died in 1864. Berkeley House eventually fell on hard times. By the start of the twentieth century, the area that once made up the Old Town of York became industrial. Many of the old homes of York's finest, earliest, families were converted to be used for different trades. At some point, both a lumber company and a grain elevator sat next to Berkeley House. Berkeley House was eventually demolished in 1925. Photographs taken just before the demolition, like this one from 1924, show the exterior stucco falling away in clumps, and the window shutters hanging from the building’s rotting window frames.

|

| This photograph from 1924 shows Berkeley House in poor condition. The historic house would be demolished the following year. |

After Berkeley House was demolished, its foundations were encased beneath a concrete parking lot until 2013. Then, work began on the construction of a new headquarters for the Globe and Mail newspaper. Work on the new 17-storey building was put on hold, while an archaeological dig could be carried out.

______________________________________________

After several years of being a "work in progress", I've finally completed a book on the earliest history of Toronto. It's called "Muddy York : A History of Toronto Until 1834". The story of the duel between John White and John Small is just one of many interesting tales to be told from this period, and it's included in my book.

For more information, or to acquire a copy, please visit the Muddy York Walking Tour website here, join our facebook group here, or email me at richard@muddyyorktours.com. Information on the book's availability should be posted by the middle of January, 2016.

______________________________________________

Thanks to everyone who has read and followed my history stories online here, over 2015 and before. If you celebrate Christmas, I hope you have a happy one, without any sort of calamity that involves your getting into a fatal duel. Please accept my best wishes for a very happy and prosperous 2016.

______________________________________________