In anticipation of Remembrance Day this coming Thursday, November 11th, I've been reflecting on some of the various military monuments in Toronto. Perhaps one of the most outstanding military monuments in Toronto is the one on Queen Street West at University Avenue, which commemorates those who fought and died in the South African War, or Second Boer War, between 1899 and 1902.

The two combatants in the conflict were the various forces of the British Empire, and the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of the two Boer republics - the South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal Republic, and the Orange Free State - in what is now South Africa. The South African War, or Boer War, was the last great conflict of imperial British expansion. For several decades, there had been intermittent conflicts between the British and the Boers, over possession of the land. Essentially, the Boers, who were Dutch speaking colonial farmers, wanted independence, and the British wanted the land.

After suffering some humiliating defeats at the outset of the war, the British eventually prevailed and the last of the Boers surrendered in May of 1902. The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on May 31st, 1902, ending the conflict. It was an expensive victory for the British, who paid out £3-million to the Boers to aid in their reconstruction. The British also extended a limited form of self government, which started to be phased in about five years after the official end of the conflict. However, both the South African Republic and the Orange Free State ceased to exist as independent republics; they were swallowed up by the British Empire and eventually replaced by the Union of South Africa in 1910.

There were many vicious elements to the conflict. By the end of 1900, the British were nominally in control of most of the Boer territory. However, the Boers reverted to tactics of guerilla warfare. British control and pacification of an area would last only as long as regular professional soldiers stayed in place; as soon as they were redeployed, locally supported guerilla soldiers would rise up and do as much damage as possible. In reprisal, the British forces - including Canadian soldiers - employed harsh tactics. We used a "scorched earth" policy, burning homes and farms to both deprive guerilla soldiers of supplies and shelter, and to destroy their morale. When met with continued resistance, we burnt the enemy - along with his family and neighbours - out of house and home. It's a simple tactic, really, and one that's probably as old as war itself, but it's not the sort of campaign that we look back on with pride.

Crops were destroyed, livestock was slaughtered, homes and farms were burned to the ground, fields were salted, to prevent them from being replanted, and wells were poisoned ... all to stop the Boer guerillas from being able to resist. But the worst was yet to come. Women and children were gathered up in the tens of thousands and forced to move into refugee camps. The Spanish had used internment camps when fighting the Americans, and the Americans themselves used such camps when fighting the Philippines, at the same time that the British (and Canadians) were fighting the Boers. But the use of the camp system in South Africa was the first time that a whole nation of people had been targeted. Entire vast areas of the country had people ripped up and moved away. Eventually, 45 camps would be built for the Boer population and 64 camps would be constructed for Black Africans. Approximately 28,000 Boer men were captured during the conflict; over 25,000 of these were shipped overseas, out of the country. Those that were left behind - the women and the children - stayed behind in refugee camps, and 26,000 of the women and children would die in these camps.

The South African or Boer War is not a conflict that's discussed much these days; from what I remember of grade school history class, it's possible that we may have glazed over it, but it doesn't really stand out in memory. And to think that Canadian soldiers would have taken part in such a conflict is certainly cause for discomfort. But it's a part of our national history. Some Canadians were enthusiastically in favour of supporting "the motherland" - in many ways, we were a British nation over one-hundred years ago, and Toronto was definitely a very British city.

But Canadian support for the South African War was controversial, even back then. The Prime Minister at the time, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, was personally opposed to Canadian involvement in the war, but he faced two opposing viewpoints among the general population. Many English Canadians felt that we should fully support the British, while many French Canadians were directly opposed to Canadian involvement in the conflict. The French even felt sympathy for the Boers, whom they viewed as a minority group fighting off the expansions of British colonialism. Laurier eventually compromised, and agreed to allow volunteers to go and fight overseas. Those who wanted to, could go and fight, but no one would be forced into service. The Canadian government would pay for their equipment and transportation, but the British government was responsible for bringing them back home again. There were over 8,000 Canadians who did volunteer to go and fight, though not all of them saw active service. Some arrived after the conflict was over, with some staying on to serve in the paramilitary South African Constabulary. Some Canadians replaced British soldiers doing garrison duty in Halifax, so the British themselves could go overseas to fight against the Boers. About 250 Canadians were wounded in the South African War, with slightly more than that dying in the fight. Of the 267 Canadian soldiers who died, only 89 were actually killed in combat duty. About 135 were killed by disease, with the remainder dying of accidental injury. In many ways, Laurier's attempt at compromise alienated both sides of the argument. Those who felt that Canadians had no place fighting off in South Africa were angry that anyone went at all, and those who wanted to support the British were angry that we didn't do enough.

When the war began in 1899, Queen Victoria was still on the throne. When the war ended three years later, her son had succeeded her, reigning as King Edward VII. It was a changing time. The British relied completely on her own troops, or those from the nations in her Empire, to fight the Boers, but after the war in South Africa, the British government began casting around for treaties and agreements with other nations. This led to the agreements with the governments of France, Russia and Japan that would later form the coalitions that fought the First World War, less than fifteen years after the South African War was over. The fight against the Boers was Britain's last real imperial, colonial conflict before the earth shattering wars of the twentieth century.

Here at home, Canadians were beginning to question their ongoing relations with the British, and there was a quest for more national independence. However, when Britain entered the First World War in 1914, we also declared war the very same day. It wasn't until the Second World War begain in 1939 that the Canadian government deliberated, declaring war a full week after the British had already done so. And more than a century after the Boer War ended in 1902, Canadian military personnel are still stationed across the globe. Canadian military engagements don't seem to give way to the same debates as those of the Americans, but there are some who, in 2010, question the presence of Canadian forces in nations like Afghanistan, just like those who wondered what we were doing in South Africa in 1899.

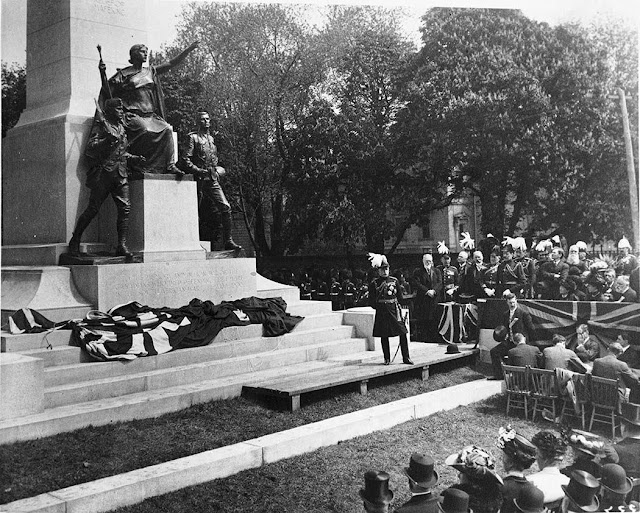

In 1908, a monument to those who fought in the South African or Boer War was unveiled along Queen Street West, at University Avenue. There to see it opened was General (later Field Marshal) John French, the First Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC. Along with Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, and General Sir Douglas Haig, French's name would enter into the annals of First World War history. He disagreed with both men about the placement of troops during that four year conflict.

Below are some photographs of Toronto's South African War monument, from the time that it was unveiled, up until the present day.

WALTER SEYMOUR ALLWARD

The South African War memorial in Toronto was designed by Walter Seymour Allward, who would become one of the most noted monument sculptors in Canadian history. Born in Toronto in November of 1876, he got his first job at the age of 14, working as an assistant to his father, who was a carpenter. Later jobs included an apprenticeship with Gibson and Simpson, an architectural firm, as well as a position at the Don Valley Brickworks, where he sculpted architectural ornaments. He showed an early skill at working with clay molds, and the experience that he gained while still young prepared him for a career as a grand creator of monuments.

Walter Allward left his mark on the City of Toronto, designing several monuments both in this city and around Canada. Noted for his sweeping historical and military monuments, his most famous work is perhaps the monument to Canadian soldiers at Vimy, which was unveiled in the summer of 1936 by King Edward VIII. He greatly influenced the work of a later sculptor, Emmanuel Hahn, who would go on to design the sculpture of Sir Adam Beck, which stands across Queen Street from Allward's South African War memorial. Hahn also did the statue of Ned Hanlan, which is now located at Hanlan's Point, on the Toronto Islands. Allward bequeathed many of his tools to Emmanuel Hahn, whom he considered his protege. In turn, Hahn passed them off to Elizabeth Bradford Holbrook, who in turn left them to a contemporary Canadian sculptor, Christian Cardell Corbet.

WALTER SEYMOUR ALLWARD

The South African War memorial in Toronto was designed by Walter Seymour Allward, who would become one of the most noted monument sculptors in Canadian history. Born in Toronto in November of 1876, he got his first job at the age of 14, working as an assistant to his father, who was a carpenter. Later jobs included an apprenticeship with Gibson and Simpson, an architectural firm, as well as a position at the Don Valley Brickworks, where he sculpted architectural ornaments. He showed an early skill at working with clay molds, and the experience that he gained while still young prepared him for a career as a grand creator of monuments.

|

| THEN : Walter Seymour Allward, one of the most noted sculptors in Canadian history. |

Walter Allward left his mark on the City of Toronto, designing several monuments both in this city and around Canada. Noted for his sweeping historical and military monuments, his most famous work is perhaps the monument to Canadian soldiers at Vimy, which was unveiled in the summer of 1936 by King Edward VIII. He greatly influenced the work of a later sculptor, Emmanuel Hahn, who would go on to design the sculpture of Sir Adam Beck, which stands across Queen Street from Allward's South African War memorial. Hahn also did the statue of Ned Hanlan, which is now located at Hanlan's Point, on the Toronto Islands. Allward bequeathed many of his tools to Emmanuel Hahn, whom he considered his protege. In turn, Hahn passed them off to Elizabeth Bradford Holbrook, who in turn left them to a contemporary Canadian sculptor, Christian Cardell Corbet.

Below are some photographs of just a few of Allward's most noted Canadian projects.

|

| THEN : Allward's sculpture for the memorial in Toronto's Victoria Square Memorial Park, the oldest cemetery in Toronto and the final resting place of many of those who were killed during the War of 1812. It was also where Katherine, the young daughter of John Graves Simcoe and his wife Elizabeth was laid to rest, after she died in infancy. Allward's monument was unveiled in 1903. This photograph is dated 1913. |

|

| NOW : A recent photograph of Allward's monument in Victoria Square Memorial Park. |

|

| THEN : Allward's monument to John Graves Simcoe was unveiled at Queen's Park in 1905. Seen above is a photograph from the unveiling. |

|

| NOW : Allward's statue of Simcoe at Queen's Park, today. |

|

| NOW : Allward's Bell Telephone Memorial, unveiled in 1917 in Brantford's Alexander Graham Bell Gardens. |

|

| THEN : The unveiling of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, in July 1936, in Vimy, France. The original ceremony was attended by King Edward VIII, and more than 50,000 Canadian veterans and their families. After undergoing years of restoration, the monument was rededicated by Queen Elizabeth II in 2007, to commemorate the ninetieth anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. |

|

| NOW : A contemporary photograph of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. |

|

| THEN : A detail of the sculpting of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. |

|

| THEN : A detail of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. |

|

| THEN : A detail of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. |

|

| NOW : A detail of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. |

You can read the full text of Her Majesty the Queen's speech, delivered for the rededication of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in 2007, here :

|

| THEN : H.M. the Queen and H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh, with Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin at the rededication of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in 2007. |

_________________________________________________________

I'll be posting more material throughout the week, in observance of Remembrance Day this Thursday, November 11th, 2010. For more information on Remembrance Day events taking place across Toronto this week, please visit the following link.

_________________________________________________________

Thank you for your wonderful post about Allward. But I think there is a problem with the unveiling date of the South Africa War Memorial. All the scholars say this Memorial was unveiled in 1910 but you date the unveiling ceremony in 1908. We can see a picture in which the monument has not jet the back pillar of the Victory. Maybe there were a double unveiling ceremony: the first time, without the tall pillar in 1908, the second time the complete memorial. What do you think?

ReplyDeleteHmm, thanks for pointing it out. The 1908 ceremony might have been unveiling the cornerstone, with the 1910 ceremony for the finished product. I am working on an article about the Old City Hall Cenotaph, which will hopefully be posted this Sunday, for Remembrance Day, and the foundation was laid about a year before the finished monument was unveiled. And with that one, they had another smaller ceremony after the Second World War and the Korean War.

ReplyDeleteMy husband's Grandfather is in the photo with the veterans at the memorial. How can I get a copy without printing off computer? Can anyone help?

ReplyDelete